Normandy

Adelaide of Normandy

Robert I "le

Magnifique"

Adelaide was an illegitimate child of Robert I, duke of Normandy, as was

William the Conqueror. William's mother is accepted to be a woman named

Herleve, and some creditable sources (e.g. The Complete Peerage vol 1 p351 (George

Edward Cokayne, enlarged by Vicary Gibbs, 1910)) claim that Adelaide had the

same mother, based, it seems on a statement by Robert de Torigny in Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges - Torigny) book VIII p327, that Adelaide was William's "soror uterina" (uterine sister) which

on the face of it would indicate the same mother, although historians

disputing this point out the de Torigny uses this same phrase in other

instances describing half-siblings whose mothers are known to be different.

Furthermore, de Torigny, in his Chronicles, expressly states that William

and Adelaide were born of different concubines.

Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges - Torigny) book VIII p327 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914)

Interpolation

de Robert de Torigny

Roberto autem, filio Ricardi, successit filius suus primogenitus,

natus ex quadam filiarum Wallevi, comitis Huntedoniae (2). Habuit enim

idem Wallevus tres filias ex uxore sua, filia comitissae de Albamarla;

quae comitissa fuit soror uterina Willelmi regis Anglorum senioris.

(2) Robert, frère de Gilbert 1er de Tunbridge,

épousa une fille de Waltheof, comte de Northampton et d’Huntingdon.

Voir Orderic, t. III, p. 402. Waltheof lui-même avait épousé Judith,

fille de la comtesse d’Aumale Aelize qui était la sœur utérine du

Conquérant.

This roughly translates as:

Interpolation of Robert de Torigny

But Robert, the son of Richard, was succeeded by his eldest son, born of

one of the daughters of Waltheof, Earl of Huntingdon (2). For the same

Waltheof had three daughters by his wife, the daughter of the countess

of Albamarla; which countess was the maternal sister of William the

Elder, king of England.

(2) Robert, brother of Gilbert I of Tunbridge, married a daughter

of Waltheof, Earl of Northampton and Huntingdon. See Orderic, Vol. III,

p. 402. Waltheof himself had married Judith, daughter of the countess of

Aumale Aelize, who was the Conqueror's half-sister.

Roberti

de Monte Auctarium A. 960-1052 in Monumenta

Germaniæ Historica vol 6 p478 (ed. G. H. Pertz, 1844)

1026.

Mortuo Ricardo secundo duce Normannorum, filio primi Ricardi,

successit ei filius eius Ricardus tercius. Hic genuit Nicolaum, postea

abbatem Sancti Audoeni, et duas filias, Papiam videlicet uxorem

Walterii de Sancto Walerico, et Aeliz, uxorem Ranulfi vicecomitis de

Baiocis. Hic tercius Ricardus eodem primo anno ducatus sui mortuus

est, et successit ei Robertas frater eius, qui genuit Willelmum de

Herleva non sponsata, qui postea Angliam conquisivit, et imam filiam

nomine Aeliz de alia concubina.

This roughly translates as:

This third Richard died in the same first year of his dukedom, and was

succeeded by his brother Robert, who fathered, by Herleva, William, who

afterwards conquered England, and a second daughter named Aeliz by

another concubine.

Enguerrand

II, count of Ponthieu

Enguerrand was the son of Hugues de Ponthieu and Bertha d'Aumal. At the Council

of Reims in 1049, when the marriage of William

(later the Conqueror) with Matilda

of Flanders was prohibited based on consanguinity, so was that of

Enguerrand, who was already married to Adelaide. Adelaide's marriage was

apparently annulled at that time, although Adelaide seems to have still

retained Enguerrand's lands in Aumale in dower after his death in an ambush

at St. Aubin, near Arques, in 1053.

Lambert

de Boulogne

Eudes,

count of Champagne

Eudes was deprived of Champagne by his uncle Thibaut before 1071. He died in

prison following a failed rebellion against William

II, probably in 1108.

Countess of Aumale. She is

mentioned in Domesday Book as "Comitissa de Albamarla", holding some manors

in Essex and Suffolk.

The Complete Peerage vol 1 pp351-2 (George

Edward Cokayne, enlarged by Vicary Gibbs, 1910)

ADELAIDE(a)

or ADELIZ, sister of William the Conqueror(b)

being illeg. da. of Robert, Duke of the Normans, by Herleve or Harlotte,

da. of Fulbert or Robert, a pelliparius of Falaise, is mentioned

in Domesday as Comitissa de Albamarla, and as holding some

manors in Essex and Suffolk. In 1082, William, King of the English, and

Maud, his wife, gave to the Abbey of La Trinité at Caen the bourg of Le

Homme (de Hulmo) in the Côtentin, “sed et Comitissa A. de

Albamarla concedente eo videlicet pacto ut ipsa teneret in vita sua.” (c)

Adelaide m., 1stly, Enguerrand II, COUNT OF PONTHIEU,

who d. s.p.m., being slain in 1053.(d) She m.,

2ndly, Lambert, (a) COUNT OF LENS

in Artois, who d. s.p.m., being slain in 1054. She m.,

3rdly, Eudes, (b) the disinherited COUNT OF CHAMPAGNE,

who had taken refuge in Normandy.(c) She d. before

1090.(d) Her husband obtained Holderness after the date of

Domesday. (e) Having conspired against William II in 1094, he

was imprisoned in 1096. He occurs as Comes Odo in the Lindsey

Survey (1115-18).

(a) For some discussion on mediæval English names, see

vol. iii, Appendix C. V.G.

(b) The pedigree of the earlier possessors of Aumale

has been investigated by T.Stapleton in Archaeologia, vol. xxvi,

pp. 349-360. There he supposed he had proved that Orderic was wrong in

stating that the wife of Count Eudes of Champagne was da. of Duke

Robert, and, that she was really the Duke’s grand-daughter. Later on, he

discovered his own error. His amended conclusions are in Coll. Top.

et Gen., vol. vi, p. 265, and, at greater length, in Rot.

Scacc. Norm., vol. ii, pp. xxix-xxxi. He had, however, in the

meantime misled Poulson (Holderness, vol. i, p. 24 sqq.).

(c) Gallia Christ., vol. xi, instr.,

c. 68-72. Stapleton always misdates this charter.

(d) A charter of the Church of St. Martin, at Auchy

(now Aumale), narrates its foundation “a viro quodam videlicet

Guerinfrido qui condidit castellum quod Albamarla nuncupatur in externis

partibus Normannie super flumen quod Augus dicitur,” this charter being

drawn up “jussu Enguerrani consulis qui filius fuit Berte supradicti

Guerinfridi filie et Adelidis comitisse uxoris sue sororis scilicet

Wilielmi Regis Anglorum,” and mentioning “Addelidis comitissa supradicti

Engueranni et supradicte Adelidis filia que post obitum illorum in

imperio successit,” and also “Judita comitissa domine supradicte filia.”

(Archaeologia, ibid., pp. 358-60). As to Judith, in the Vita

et passio venerahilis viri Gualdevi comitis Huntendonie et Norhantonie

(an MS. of the 13th century in the Douai library), printed by F. Michel,

Chron. Anglo-Normandes, vol. ii, it is stated, p. 112, that King

William gave to Waltheof “in uxorem neptem suam Ivettam, filiam comitis

Lamberti de Lens, sororem nobilis viri Stephani comitis de Albemarlia.”

The following pedigree illustrates this descent.

Guerinfrey. He

built the castle of Aumale. =

|

Berthe, da. and h. = Hugh II, Count of Ponthieu. d. 20 Nov.

1051.

|

Enguerrand, Count of Ponthieu and Sire d'Aumale. Slain at the siege of

Arques in 1053.

= 1. Adelaide, sister of William the Conqueror. She is styled Countess

of Aumale. d. before 1090.

|

Adelaide.

Living 1096

= 2. Lambert de Boulogne. Count of Lens. Slain in battle at Lille in

1054.

|

Judith,

m. Waltheof, Earl of Huntingdon.

= 3. Eudes, Count of Champagne; deprived of Champagne by his uncle

Thibaut before 1071.

|

Stephen, Count 1096. of Aumale.

(a) He was yr. s. of Eustace I, Count of Boulogne, by

Mahaut, da. of Lambert I, Count of Louvain.

(b) He was s. and h. of Stephen II, Count of

Champagne, by Adele, whose parentage is unknown.

(c) A charter to the Church of St. Martin at Auchy,

was written by command of Adelidis the most noble Comitissa,

sister to wit of William, King of the English, “confirmante viro suo

videlicet Odone comite una cum filio suo Stephano.” (Stapleton, Rot.

Scacc. Norm., vol. ii, p. xxxi).

(d) It is here assumed that it was the sister of the

Conqueror, and not her da. of the same name, who is mentioned in

Domesday. Stapleton says of the former that “she did not long survive

her br.. King William,” but there is nothing definite known beyond that

she was living in 1082 and dead in 1090. There seems to be no charter in

which the younger Adelaide is called Countess. The charter of her

half-brother, Stephen, dated 14 July 1096, is “consensu simul et

corroboratione sororis mee Adelidis,” showing she had some rights on

Aumale. It is not very clear what they were, though she is said in the

charter quoted above to have succeeded “in imperio.” Nothing further

seems to be known about her, but Count Stephen had eventually the whole

inheritance.

(e) Count Eudes and his s., Stephen, gave the manor

and church of Hornsea (in Holderness) to the Abbey of St. Mary at York.

(Monasticon, vol. iii, p. 548).

The Conqueror and his companions vol 1 pp122-6

(James Robinson Planché, 1874)

Enguerrand, or

Ingleram, Sire d’Aumale in right of his mother, who married Adelaide,

sister of the Conqueror, and was killed in an ambush at St. Aubin, near

Arques, in 1053, leaving an only daughter, named Adelaide after her

mother, and having settled on his wife the lands of Aumale in dower. The

widow of Enguerrand, being still young, married secondly, and in

the first year of her widowhood, Lambert, Count of Lens, in Artois, and

brother of Eustace II., Count of Boulogne, and had by him a daughter,

named Judith, whose hand was given by her uncle, William the Conqueror,

to Waltheof, Earl of Northumberland. Count Lambert could scarcely have

seen the birth of his child, for he was killed at Lille the following

year, in a battle between Baldwin, Count of Flanders, and the Emperor

Henry III. A widow for the second time, and still in the prime of life,

she married, thirdly, Odo of Champagne, by whom she was the mother of

Stephen, who, on the death of his elder sister Adelaide, became the

first Comte d’Aumale, or Earl of Albemarle, the Seigneurie having been

made a Comte by King William, but upon what occasion and at what time we

have no evidence.

The name of Adeliza with the title of “Comitissa de Albemarle”

occurs in Domesday, but not that of Odo, which first appears in

connection with English transactions in 1088 (1st of William Rufus),

when Count Odo and his son Stephen gave the manor and church of Hornsea,

in the wapentake of Holderness, to the Abbey of St. Mary of York.

… Whether the expatriated Count of Champagne fleshed his maiden sword at

Senlac or not, he appears to have made no mark either for good or for

evil in the annals of this country till, misled by ambition, he was

induced to join in the conspiracy the collapse of which has given him an

unenviable reputation in them.

History is quite silent about him until after the death of the

Conqueror, when we are told that Odo found himself embarrassed by his

position as a feudatory of William Rufus in England and of Robert

Court-heuse in Normandy. He owed allegiance to each; but how could he

serve two masters who were at war with one another? He decided in favour

of Rufus, and received an English garrison in his Castle of Aumale,

which, in conjunction with his son Stephen, he enlarged and

strengthened, at the expense of the royal treasury, on the invasion of

Normandy by the Red King in 1090.

Five years afterwards, however, he joined in a conspiracy with

Robert de Mowbray, William d’Eu, and other disaffected nobles, to depose

Rufus and place his own son Stephen d’Aurnale upon the throne.

The conspiracy failing in consequence of timely warning having

been given to the King, Odo and his son were both arrested, the former

thrown into a prison, from which he never emerged alive, and the latter

condemned to have his eyes put out; but the piteous prayers of his wife

and family, to say nothing of the payment of a considerable sum of

money, obtained a remission of his sentence and restoration to liberty.

How long Odo lingered in his dungeon is unknown. The exact date of his

death is as uncertain as nearly every other part of his history, but it

is presumed to have taken place in 1108.

- Roberti de Monte Auctarium A. 960-1052 in

Monumenta Germaniæ Historica vol 6 p478

(ed. G. H. Pertz, 1844); The Complete Peerage vol 1 p351

(George Edward Cokayne, enlarged by Vicary Gibbs, 1910); The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Robert I "le

Magnifique"); Medieval

Lands (ADELAIS)

- The Complete Peerage vol 1 p351

(George Edward Cokayne, enlarged by Vicary Gibbs, 1910); The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Robert I "le

Magnifique"); Annulment of marriage from wikipedia

(Adelaide of Normandy); Enguerrand parents from Medieval

Lands (ENGUERRAND); Enguerrand death from The Conqueror and his companions vol 1

p122 (James Robinson Planché, 1874) and The Complete Peerage vol 1 p351

(George Edward Cokayne, enlarged by Vicary Gibbs, 1910)

- The Complete Peerage vol 1 p351

(George Edward Cokayne, enlarged by Vicary Gibbs, 1910); The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Robert I "le

Magnifique")

- The Complete Peerage vol 1 p352 (George

Edward Cokayne, enlarged by Vicary Gibbs, 1910); Medieval

Lands (ADELAIS); wikipedia

(Lambert II, Count of Lens)

- The Complete Peerage vol 1 p351

(George Edward Cokayne, enlarged by Vicary Gibbs, 1910); The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Robert I "le

Magnifique"); Eudes disinherited from The Complete Peerage vol 1 p351n

(George Edward Cokayne, enlarged by Vicary Gibbs, 1910); Eudes notes and

death from The Conqueror and his companions vol 1

p126 (James Robinson Planché, 1874)

- The Complete Peerage vol 1 p351

(George Edward Cokayne, enlarged by Vicary Gibbs, 1910); The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Robert I "le

Magnifique")

- The Complete Peerage vol 1 p351 (George

Edward Cokayne, enlarged by Vicary Gibbs, 1910); The Conqueror and his companions vol 1

p122 (James Robinson Planché, 1874); Medieval

Lands (ADELAIS); wikipedia

(Adelaide of Normandy)

- Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book VIII p327 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914); The Complete Peerage vol 1 pp351-2

(George Edward Cokayne, enlarged by Vicary Gibbs, 1910); The Conqueror and his companions vol 1

pp122-6 (James Robinson Planché, 1874); Medieval

Lands (ADELAIS); wikipedia

(Adelaide of Normandy)

Gunnor

Richard I of

Normandy

Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book IV pp68-9 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914)

XVIII

[XVIII]

Qua tempestate (2) Emma, uxor ejus, filia Magni Hugonis,

moritur absque liberis. Ipse vero non multo post quamdam

speciosissimam virginem, nomine Gunnor (3), ex nobilissima Danorum

prosapia ortam, sibi in matrimonium christiano more desponsavit, ex

qua filios genuit, Ricardum (4) videlicet et Rodbertum (5) atque

Malgerium (6), et duos alios (7), necnon filias tres. Quarum una,

nomine Emma (1), Edelredo, regi Anglorum, nupsit, de qua idem rex

Edwardum regem necnon Alvredum, Goduini comitis longo post dolis

interemptum, procreavit. Secunda vero (2), Hadvis vocata, Goiffredo

Britannorum juncta comiti, Alannum et Eudonem duces progenuit. Tertia

quidem comiti Odoni, nomine Mathildis (3), de qua sermo orietur in

posteris.

(2) Dudon, IV, 125, p. 288-289. Mais, dans ce chapitre, à

partir de: «Ex qua duos filios», Guillaume de Jumièges ne suit plus

Dudon.

(3) L’origine de Gonnor semble avoir été en réalité moins

noble. Cf. infra le récit que Robert de Torigny nous a laissé

de la rencontre de Gonnor et de Richard 1er.

(4) Le futur Richard II.

(5) Robert, archevêque de Rouen de 989 à 1037.

(6) Mauger qui devint plus tard comte de Corbeil par son

mariage avec la fille du comte Aimon. Mauger fut le père ou le

grand-père de Guillaume Guerlenc, comte de Mortain.

(7) Geoffroi, comte de Brionne, est l’un de ces deux fils.

(1) Emme, femme du roi d’Angleterre Ethelred, qui monta sur le

trône en 978, fut chassé d’Angleterre en 1013 par le Danois Suénon, et

mourut en 1016.

(2) Havois ou Havoise épousa Geoffroi 1er, comte de

Rennes, de 992 à 1008.

(3) Voir sur le mariage de Mathilde avec Eudes de Chartres, infra,

livre V, chap. X.

This roughly translates as:

XVIII [XVIII]

At which time (2) Emma, his wife, daughter of Hugh the Great,

died childless. But not long after, he betrothed to himself in Christian

marriage a very beautiful maiden, named Gunnor (3), of the noblest

lineage of the Danes, by whom he had sons, namely Richard (4) and

Rodbert (5) and Mauger (6), and two others (7), as well as three

daughters. One of whom, named Emma (1), married Ethelred, king of the

English, by whom the same king begat King Edward and Alfred, who was

long after slain by the deceit of Earl Godwin. But the second (2),

called Hadvis, married Earl Geoffrey of the Britons and bore him the

dukes Alan and Eudon. The third, indeed, to Earl Odo, named Mathilde

(3), of whom there will be a story in posterity.

(2) Dudo, IV, 125, pp. 288-289. But, in this chapter, starting

with "Ex qua duos filios," William of Jumièges no longer follows Dudo.

(3) Gonnor's origins seem to have been less noble in reality. See

below the account that Robert of Torigny left us of the meeting of

Gonnor and Richard I.

(4) The future Richard II.

(5) Robert, Archbishop of Rouen from 989 to 1037.

(6) Mauger, who later became Count of Corbeil through his

marriage to the daughter of Count Aimon. Mauger was the father or

grandfather of William Guerlenc, Count of Mortain.

(7) Geoffroi, Count of Brionne, is one of these two sons. (1)

Emme, wife of King Ethelred of England, who ascended the throne in 978,

was driven from England in 1013 by the Dane Suénon, and died in 1016.

(2) Havois or Havoise married Geoffrey I, Count of Rennes, from

992 to 1008.

(3) See on the marriage of Matilda to Eudes of Chartres, infra,

Book V, Chapter X.

Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges - Torigny) book VIII pp322-3 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914)

INTERPOLATIONS

DE ROBERT DE TORIGNY

[XXXVI]

Relatio quomodo ipsa Gonnor primo Ricardo, duci Normanniae

copulata fuerit matrimonio.

Et quia (6) de Gunnore comitissa fecimus mentionem, causa

matris Rogerii de Monte Gummerii, quae fuit neptis ejusdem comitissae,

libet litterarum memoriae commendare, sicut ab antiquis didici,

qualiter ad conjugium comitis Ricardi eadem Gunnor accesserit. Igitur

Ricardus comes, audita fama pulchritudinis conjugis cujusdam sui

forestarii, manentis haud procul ab oppido Arcarum, villa quae dicitur

Schechevilla (1), ex industria ivit venatum illuc, volens probare si

verum esset, quod relatione quorumdam perceperat. Hospitatur igitur in

domo forestarii, illectusque venustate vultus uxoris ipsius, precepit

hospiti suo quod ipsa nocte adduceret ad cubiculum suum uxorem suam

Sainfriam: sic enim vocabatur. Quod cum ille eidem tristior

retulisset, illa, ut sapiens mulier, consolata est eum, dicens

supposituram in loco suo Gunnorem, sororem suam, virginem quamplurimum

seipsa pulchriorem. Quod et factum est. Cognita denique tali fraude,

delectatus est dux, quod non incurrisset peccando in alienam uxorem.

Genuit itaque ex Gunnore filios tres, et totidem filias, ut in libro,

qui de gestis ejusdem ducis scriptus est, superius invenitur (2). Cum

vero idem comes quemdam filium suum, nomine Robertum, vellet fieri

archiepiscopum Rothomagensem, responsum est ei a quibusdam hoc

nullatenus secundum scita canonum posse esse, ideo quod mater ejus non

fuisset desponsata. Hac itaque causa comes Ricardus Gunnorem

comitissam more christiano sibi copulavit, filiique, qui jam ex ea

nati erant, interim dum sponsalia agerentur, cum patre et matre pallio

cooperti sunt, et sic postea Robertus factus est archiepiscopus

Rothomagensis.

(6) Robert de Torigny semble utiliser ici des traditions

circulant dans la famille de Montgommery. Ce récit sur les origines de

Gonnor semble assez plausible, bien qu’à la vérité il ne soit confirmé

par aucun texte contemporain.

(1) Sauqueville est situé non loin d’Arques.

(2) Guillaume de Jumièges, livre IV, chap. [XVIII].

This roughly translates as:

INTERPOLATIONS OF ROBERT DE TORIGNY

[XXXVI]

An account of how the same Gunnor was first married to

Richard, Duke of Normandy.

And because (6)

we have made mention of countess Gunnor—on account of the mother of

Roger de Montgomery, who was the niece of the same countess—it is

pleasing to commit to written memory, just as I learned from the

ancients, how this same Gunnor came to her marriage with Count Richard.

Therefore count Richard, having heard reports of the beauty of

the wife of a certain forester of his who lived not far from the town of

Arques, in a village called Sevis (Schechevilla) (1), went there to hunt

on purpose, wishing to test if what he had heard from others was true.

He was entertained, therefore, in the house of the forester; and being

enticed by the charm of the wife's face, he commanded his host that he

should bring his wife, Sainfria (for so she was called), to his

bedchamber that very night.

When the forester sadly reported this to her, she, being a wise

woman, comforted him, saying that she would put in her place her sister

Gunnor, a virgin much more beautiful than herself. And so it was done.

When the deception was finally made known, the Duke was delighted that

he had not incurred sin by taking another man's wife.

He thus begot by Gunnor three sons and as many daughters, as is

found earlier in the book written about the deeds of the same duke (2).

But when the count wished for a certain son of his, named Robert, to be

made archbishop of Rouen, he was told by some that this could in no way

be done according to canon law because his mother had not been formally

wedded.

For this reason, count Richard joined countess Gunnor to himself

in marriage according to Christian custom. The sons who had already been

born to her were, while the marriage rites were being performed, covered

with a cloak (pallio) along with their father and mother; and thus,

Robert was afterwards made archbishop of Rouen.

(6) Robert de Torigny seems to be using traditions circulating in

the Montgomery family. This account of Gonnor's origins seems quite

plausible, although it is not, in truth, confirmed by any contemporary

text.

(1) Sauqueville is located not far from Arques.

(2) William of Jumièges, book IV, chapter [XVIII].

Countess of Rouen

Gunnor was countess by marriage to Richard I of Normandy. She functioned as

regent of Normandy during the absence of her spouse, as well as the adviser

to him and later to his successor, their son Richard II.

|

|

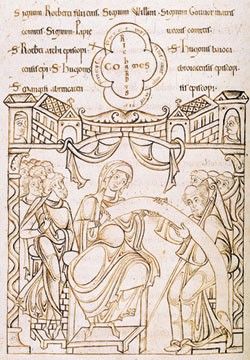

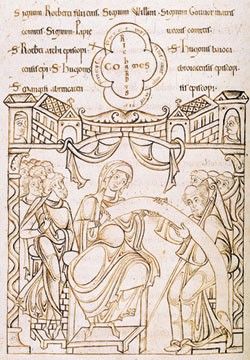

A representation of Gunnor granting her

charter to the abbot and monks of Mont St. Michel, from the abbey

cartulary. She is represented in the company of her son Robert the

Dane, archbishop of Rouen.

|

By charter, Gunnor made a gift of the vills of Britavilla and Domjean, which

were in her dower, to the abbey of Mont St Michel

Calendar of documents preserved in France vol

1 p250 (ed. J. Horace Round, 1899)

[N. D.]

(Cartulary,2 fo. 24.Trans. Vol. II. fo. 215.)

703. Charter of Gonnor [relict of Duke Richard]. In fear

for the greatness of her crimes, and desiring the joy of life in heaven,

she delivers to Mont St. Michel and the brethren there serving God, as

their possession for ever, two alods (aloda), namely Britavilla

and Domjean (donnum Johannem) which, her husband count Richard,

of blessed memory, had given her, with more [estates], in dower; [and

this she does] chiefly for the good of his soul, and then for the weal

of her own soul and body, and then for the weal of her sons count

Richard, archbishop Robert, and others, who give their consent . . . .

These alods she bestows on the abbey, [calling] Christ and the whole

church to witness, with [their] lands, cultivated or not, churches,

mills, meadows, and all appurtenances, and with all the rents and dues

which she has possessed there to that day, to hold free of claim or

question from any of her successors, relatives or any one else. Curses

on those who infringe the gift.

[Signa] Rotberti archiepiscopi; Maalgerii; Rotberti; Hugonis

Constanciensis episcopi; Hugonis Baiocensis episcopi; Hugonis Sais

episcopi; Rogeri episcopi; Norgoti episcopi; Heldeberti abbatis;

Willelmi abbatis; Uspac abbatis; Willelmi Laici; [Signa] Rotberti

comitis; Godefridi; Willelmi; Radulfi; Tursteni; Tescelini vicecomitis;

Herluini; Anschetil vicecomitis; Willelmi filii Tursteni; Hugonis Laici;

Gerardi; Osmundi clerici; Gaufridi; Arfast; Nielli; Guimundi;

Anschitilli; Milonis; Rainaldi; Odonis; Rannulfi.

2 Also a vidimus of 1334 in the Archives. In

the Cartulary, this charter is preceded by a representation of Gonnor

granting hers to the abbot and monks, and followed by one [in two

compartments] of the death of Richard, in which the monks are seen

placing the gift on the altar for him, “per brachium sancti Autberti”

(as another charter expresses it) apparently. These drawings are copied

in d’Anisy’s Transcript. The original charter of Richard is headed:

“Carta quam comes Richardus fecit Sancto Michaeli ante obitum suum

Fiscanno.”

The ecclesiastical history of England and Normandy by

Ordericus Vitalis vol 1 p381 (trans. Thomas Forester, 1853)

In the

year of our Lord 996, on the death of Richard the elder, he was

succeeded by Richard Gonorrides his son,2

2

Gonnor was second wife of Richard I. For the singular occurrences which

introduced this lady into the ducal family, see the continuator of

William de Jumièges, book viii. c. 36.

The History Of The Norman Conquest Of England vol

1 p253 (Edward A. Freeman, 1877)

Richard, the

next Duke, and Emma, the future Lady of the English, who were

legitimated by Richard’s marriage with their mother. These were the

children of Gunnor, a woman of Danish birth, to whom different stories

attribute a noble and a plebeian origin.4 From these children

and from the kinsfolk of Gunnor, all of whom were promoted in one way or

another, sprang a large part of the Norman nobility.

4 Dudo (u. s.) makes her to be “ex famosissima

nobilium Dacorum prosapia exorta,” but he allows that the Duke “eam

prohibitæ copulationis fœdere sortitus est sibi amicabiliter.” He

marries her (“inextricabili maritalis fœderis privilegio sibi

connectit”) at the advice of the great men of the land. So William of

Jumièges (iv. 18) vouches for the nobility of her birth and for her

marriage being celebrated “Christiano more.” But his continuator (viii.

36) has a curious legend—the same as one of the legends of our Eadgar—to

tell about her first introduction to Richard. See also Roman de Rou,

5390-5429, &c., 5767-5812.

between 4 and 8 January 1031

Poppa

|

Statue of Poppa in De Gaulle square, Bayeux,

Normandy, France |

Rollo

Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book II pp23-4 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914)

Illico

(3), avulsis ab obsidione navibus, Bajocas velivolo venit cursu. Quam

captam aliquatenus subvertit, habitatoribus ejus interfectis. In qua

quamdam nobilissimam puellam, nomine Popam, filiam scilicet

Berengerii, illustris viri, capiens, non multo post more danico sibi

copulavit. Ex qua Willelmum genuit, filiamque nomine Gerloc valde

decoram (4).

(3) Dudon II, 16; Guillaume de Jumièges suit ici Dudon un peu

moins littéralement qu’à l’ordinaire.

(4) Dudon ne dit pas nettement que Poupe, fille de Bérenger,

comte de Bayeux, fut d’abord la concubine de Rollon, et s’il mentionne

la naissance du futur Guillaume Longue-Epée, il ne parle pas de

Gerloc. Il semble que c’est en 886 que les Normands s’emparèrent de

Bayeux, conduits par Siegfried et non par Rollon (voir Vogel, op.

cit., p. 336), après l’échec d’une première tentative contre

Paris.

This roughly translates as:

Immediately (3), having detached the ships from the siege, he came to

Bajocas at a gallop. When he had captured it, he somewhat overthrew it,

killing its inhabitants. In whom, capturing a certain very noble girl

named Popa, the daughter of Berenger, a distinguished man, he not long

afterwards married her in the Danish manner. By whom he begot William,

and a very beautiful daughter named Gerloc (4).

(1) Dudo II, 15, p. 156. The Normans arrived before Paris at the

end of November 885.

(2) The phrase "Quo illic… facilem capi" is not taken from Dudo.

(3) Dudo II, 16; William of Jumièges follows Dudo here a little

less literally than usual.

(4) Dudo does not clearly state that Poupe, daughter of Berengar,

Count of Bayeux, was first Rollo's concubine, and while he mentions the

birth of the future William Longsword, he does not mention Gerloc. It

seems that it was in 886 that the Normans seized Bayeux, led by

Siegfried and not by Rollo (see Vogel, op. cit., p. 336), after the

failure of a first attempt against Paris.

p31

XV [XXII]

Per idem (1) tempus morte preventa uxor ejus absque liberis

moritur, et dux repudiatam Popam, ex qua filium nomine Willelmum jam

adultum genuerat, iterum repetens, sibi copulavit.

(1) Dudon, II, 34, p. 173-174. La mort de Rollon se place en

931 ou 932.

This roughly translates as:

XV [XXII]

During the same (1) time, his wife, having been prevented by

death, dies without children, and the duke, having again sought to marry

Popa, whom he had repudiated, by whom he had had a son named William,

who was now an adult.

(1) Dudon, II, 34, p. 173-174. Rollo's death takes place in 931

or 932.

The ecclesiastical history of England and Normandy by

Ordericus Vitalis vol 1 p380 (trans. Thomas Forester, 1853)

Baieux he took

by storm, putting to the sword its count Berenger, whose daughter Poppa

he married, and had by her a son called William Longue-epee.4

1

… Rollo, who is not mentioned in any authentic account till 911, was not

present at this battle, nor at the siege of Paris. All that concerns his

taking Baieux, including count Berenger and his daughter Poppa, is still

the subject of controversy.

The History Of The Norman Conquest Of England vol

1 pp180-1 (Edward A. Freeman, 1877)

Gisla bore no

children to her already aged husband, and William was the son of a

consort who both preceded and followed her in his affections. She was

known as Popa, whether that designation was really a baptismal name or,

as some hint, a mere name of endearment. She was the daughter of a

certain Count Berengar, and was carried off as a captive by Rolf when he

took Bayeux in his pirate days.1 Her brother, Bernard Count

of Senlis, plays an important part in the reigns of his nephew and

great-nephew. Popa and her son seem to have stood in a doubtful position

which they share with more than one other Norman Duke and his mother.

Rolf and Popa were most likely married, as the phrase was, “Danish

fashion,”2 which, in the eyes of the Church, was the same as

not being married at all. A woman in such a position might, almost at

pleasure, be called either wife or concubine, and might be treated as

either the one or the other. Her children might, as happened to be

convenient, be either branded as bastards or held entitled to every

right of legitimate birth. Rolf put away Popa when he married King

Charles’s daughter, and when King Charles’s daughter died, he took Popa

back again.1

1 Dudo, 77 D; Benoit, v. 4122.

2 Will. Gem. iii. 2. See Appendix X.

1 Will. Gem. ii. 22. “Repudiatam Popam … iterum

repetens sibi copulavit.” See more in detail, Benoit, v. 7954. So Roman

de Rou, 2037.

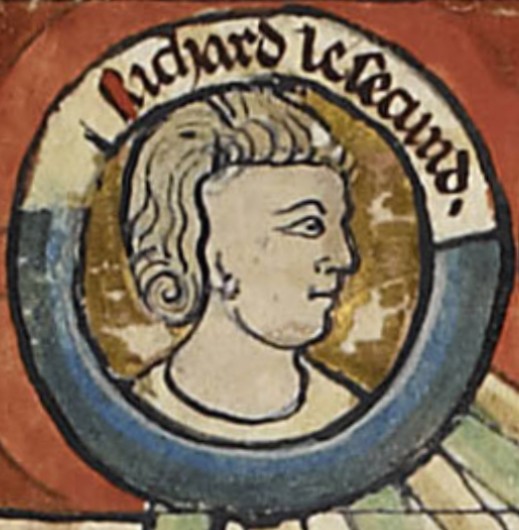

Richard I of Normandy

|

|

Richard I, duke of Normandy, as depicted

in the Genealogical chronicle of the English Kings (1275-1300) -

BL Royal MS 14 B V

|

|

Statue of Richard I "Sans-Peur" as part of

the Six Dukes of Normandy set of statues in the Falaise

town square, Normandy, France |

931 or 932

Richard was aged 10 when his father died in 942 (Orderici Vitalis Historiæ ecclesiasticæ libri tredecim

liber III vol 2 p9 (ed. Augustus Le Prevost, 1840)).

Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book III pp33-4 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914)

II [II]

… Regresso igitur eo de prelio, a prefecto Fiscannensis castri legatus

dirigitur, deferens ex quadam nobilissima puella sibi Danico more

juncta, nomine Sprota, filium esse natum. Qui, letus valde effectus,

sub festinatione Bajocas illum episcopo Henrico mandavit dirigere (1),

ut per ipsius manus sacro lotum fonte proprio nomine vocaret eum

Ricardum. Cujus jussa presul gratanter complens puerum chrismate

delibutum Fiscanum remittit nutriendum.

(1) Guillaume de Jumièges copie de travers Dudon qui veut dire que

l’évêque de Bayeux vint à Fécamp baptiser l’enfant, et non pas que

l’enfant fut envoyé à Bayeux. Voir Lair, p. 191 de l’éd. de Dudon.

This roughly translates as:

II [II]

… So when he returned from the battle, he was sent by the prefect of the

castle of Fiscan, as a legate, reporting that a son had been born to him

by a certain noble maiden, married to him in the Danish manner, named

Sprota. He, greatly distressed, in haste ordered him to be sent to

Bishop Henry of Bajocas (1), so that he might be washed by his own hands

in a holy fountain and he would name him Richard. The prefect,

gratefully fulfilling his orders, sent the child, anointed with chrism,

back to Fiscan to be raised.

(1) William of Jumièges incorrectly copies Dudon, who means that

the Bishop of Bayeux came to Fécamp to baptize the child, and not that

the child was sent to Bayeux. See Lair, p. 191 of Dudon's ed.

William Longsword

Sprota

Emma in 960

Flodoardi

annales in Monumenta Germaniæ Historica

SS 3 p405 (ed. G. H. Pertz, 1839)

Anno 960

… Richardus filius Willelmi, Nortmannorum principis, filiam Hugonis,

Transequani quondam principis, ducit uxorem.

This roughly translates as:

In the year 960

… Richard, son of William, prince of the Northmen, marries the daughter

of Hugh, formerly prince of the Seine.

Emma was the daughter of Hugh the Great. She died childless.

Gunnor

Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book IV pp68-9 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914)

XVIII

[XVIII]

Qua tempestate (2) Emma, uxor ejus, filia Magni Hugonis,

moritur absque liberis. Ipse vero non multo post quamdam

speciosissimam virginem, nomine Gunnor (3), ex nobilissima Danorum

prosapia ortam, sibi in matrimonium christiano more desponsavit, ex

qua filios genuit, Ricardum (4) videlicet et Rodbertum (5) atque

Malgerium (6), et duos alios (7), necnon filias tres. Quarum una,

nomine Emma (1), Edelredo, regi Anglorum, nupsit, de qua idem rex

Edwardum regem necnon Alvredum, Goduini comitis longo post dolis

interemptum, procreavit. Secunda vero (2), Hadvis vocata, Goiffredo

Britannorum juncta comiti, Alannum et Eudonem duces progenuit. Tertia

quidem comiti Odoni, nomine Mathildis (3), de qua sermo orietur in

posteris.

(2) Dudon, IV, 125, p. 288-289. Mais, dans ce chapitre, à

partir de: «Ex qua duos filios», Guillaume de Jumièges ne suit plus

Dudon.

(3) L’origine de Gonnor semble avoir été en réalité moins

noble. Cf. infra le récit que Robert de Torigny nous a laissé

de la rencontre de Gonnor et de Richard 1er.

(4) Le futur Richard II.

(5) Robert, archevêque de Rouen de 989 à 1037.

(6) Mauger qui devint plus tard comte de Corbeil par son

mariage avec la fille du comte Aimon. Mauger fut le père ou le

grand-père de Guillaume Guerlenc, comte de Mortain.

(7) Geoffroi, comte de Brionne, est l’un de ces deux fils.

(1) Emme, femme du roi d’Angleterre Ethelred, qui monta sur le

trône en 978, fut chassé d’Angleterre en 1013 par le Danois Suénon, et

mourut en 1016.

(2) Havois ou Havoise épousa Geoffroi 1er, comte de

Rennes, de 992 à 1008.

(3) Voir sur le mariage de Mathilde avec Eudes de Chartres, infra,

livre V, chap. X.

This roughly translates as:

XVIII [XVIII]

At which time (2) Emma, his wife, daughter of Hugh the Great,

died childless. But not long after, he betrothed to himself in Christian

marriage a very beautiful maiden, named Gunnor (3), of the noblest

lineage of the Danes, by whom he had sons, namely Richard (4) and

Rodbert (5) and Mauger (6), and two others (7), as well as three

daughters. One of whom, named Emma (1), married Ethelred, king of the

English, by whom the same king begat King Edward and Alfred, who was

long after slain by the deceit of Earl Godwin. But the second (2),

called Hadvis, married Earl Geoffrey of the Britons and bore him the

dukes Alan and Eudon. The third, indeed, to Earl Odo, named Mathilde

(3), of whom there will be a story in posterity.

(2) Dudo, IV, 125, pp. 288-289. But, in this chapter, starting

with "Ex qua duos filios," William of Jumièges no longer follows Dudo.

(3) Gonnor's origins seem to have been less noble in reality. See

below the account that Robert of Torigny left us of the meeting of

Gonnor and Richard I.

(4) The future Richard II.

(5) Robert, Archbishop of Rouen from 989 to 1037.

(6) Mauger, who later became Count of Corbeil through his

marriage to the daughter of Count Aimon. Mauger was the father or

grandfather of William Guerlenc, Count of Mortain.

(7) Geoffroi, Count of Brionne, is one of these two sons. (1)

Emme, wife of King Ethelred of England, who ascended the throne in 978,

was driven from England in 1013 by the Dane Suénon, and died in 1016.

(2) Havois or Havoise married Geoffrey I, Count of Rennes, from

992 to 1008.

(3) See on the marriage of Matilda to Eudes of Chartres, infra,

Book V, Chapter X.

Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges - Torigny) book VIII pp322-3 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914)

INTERPOLATIONS

DE ROBERT DE TORIGNY

[XXXVI]

Relatio quomodo ipsa Gonnor primo Ricardo, duci Normanniae

copulata fuerit matrimonio.

Et quia (6) de Gunnore comitissa fecimus mentionem, causa

matris Rogerii de Monte Gummerii, quae fuit neptis ejusdem comitissae,

libet litterarum memoriae commendare, sicut ab antiquis didici,

qualiter ad conjugium comitis Ricardi eadem Gunnor accesserit. Igitur

Ricardus comes, audita fama pulchritudinis conjugis cujusdam sui

forestarii, manentis haud procul ab oppido Arcarum, villa quae dicitur

Schechevilla (1), ex industria ivit venatum illuc, volens probare si

verum esset, quod relatione quorumdam perceperat. Hospitatur igitur in

domo forestarii, illectusque venustate vultus uxoris ipsius, precepit

hospiti suo quod ipsa nocte adduceret ad cubiculum suum uxorem suam

Sainfriam: sic enim vocabatur. Quod cum ille eidem tristior

retulisset, illa, ut sapiens mulier, consolata est eum, dicens

supposituram in loco suo Gunnorem, sororem suam, virginem quamplurimum

seipsa pulchriorem. Quod et factum est. Cognita denique tali fraude,

delectatus est dux, quod non incurrisset peccando in alienam uxorem.

Genuit itaque ex Gunnore filios tres, et totidem filias, ut in libro,

qui de gestis ejusdem ducis scriptus est, superius invenitur (2). Cum

vero idem comes quemdam filium suum, nomine Robertum, vellet fieri

archiepiscopum Rothomagensem, responsum est ei a quibusdam hoc

nullatenus secundum scita canonum posse esse, ideo quod mater ejus non

fuisset desponsata. Hac itaque causa comes Ricardus Gunnorem

comitissam more christiano sibi copulavit, filiique, qui jam ex ea

nati erant, interim dum sponsalia agerentur, cum patre et matre pallio

cooperti sunt, et sic postea Robertus factus est archiepiscopus

Rothomagensis.

(6) Robert de Torigny semble utiliser ici des traditions

circulant dans la famille de Montgommery. Ce récit sur les origines de

Gonnor semble assez plausible, bien qu’à la vérité il ne soit confirmé

par aucun texte contemporain.

(1) Sauqueville est situé non loin d’Arques.

(2) Guillaume de Jumièges, livre IV, chap. [XVIII].

This roughly translates as:

INTERPOLATIONS OF ROBERT DE TORIGNY

[XXXVI]

An account of how the same Gunnor was first married to

Richard, Duke of Normandy.

And because (6) we have made mention of countess Gunnor—on

account of the mother of Roger de Montgomery, who was the niece of the

same countess—it is pleasing to commit to written memory, just as I

learned from the ancients, how this same Gunnor came to her marriage

with Count Richard.

Therefore count Richard, having heard reports of the beauty of

the wife of a certain forester of his who lived not far from the town of

Arques, in a village called Sevis (Schechevilla) (1), went there to hunt

on purpose, wishing to test if what he had heard from others was true.

He was entertained, therefore, in the house of the forester; and being

enticed by the charm of the wife's face, he commanded his host that he

should bring his wife, Sainfria (for so she was called), to his

bedchamber that very night.

When the forester sadly reported this to her, she, being a wise

woman, comforted him, saying that she would put in her place her sister

Gunnor, a virgin much more beautiful than herself. And so it was done.

When the deception was finally made known, the Duke was delighted that

he had not incurred sin by taking another man's wife.

He thus begot by Gunnor three sons and as many daughters, as is

found earlier in the book written about the deeds of the same duke (2).

But when the count wished for a certain son of his, named Robert, to be

made archbishop of Rouen, he was told by some that this could in no way

be done according to canon law because his mother had not been formally

wedded.

For this reason, count Richard joined countess Gunnor to himself

in marriage according to Christian custom. The sons who had already been

born to her were, while the marriage rites were being performed, covered

with a cloak (pallio) along with their father and mother; and thus,

Robert was afterwards made archbishop of Rouen.

(6) Robert de Torigny seems to be using traditions circulating in

the Montgomery family. This account of Gonnor's origins seems quite

plausible, although it is not, in truth, confirmed by any contemporary

text.

(1) Sauqueville is located not far from Arques.

(2) William of Jumièges, book IV, chapter [XVIII].

Richard had other children by unknown mistresses.

|

|

Silver denier from the reign of Richard I

of Normandy, minted in Rouen.

Obverse: Short cross with a pellet in each quadrant, with

"RICARDVSI" around.

Reverse: X with a church roof surmounted by a cross, with pellets

between the arms of the X, with "ROTO MAGVS" around.

|

Leader of the Normans of Rouen,

942-996.

Richard was minor when his father William was assassinated in 942. It was

largely during Richard's long period of rule that what eventually became the

duchy of Normandy evolved from what was essentially a pirate principality

into a feudal state. Richard is described by such a wide range of words (comes,

marchio, consul, princeps, dux) by various sources that it would be

difficult to argue that there is a specific "title" by which he should be

called. Richard was succeeded by his son Richard II in 996.

Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book IV pp69-71 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914)

XIX [XIX]

Cum igitur (4) dux Ricardus multorum operum bonorum polleret

incrementis, inter plurima commercia summae opinionis, apud Fiscannum

mirae magnitudinis et pulchritudinis in honore Deificae Trinitatis

templum construxit, mirificisque ornamentis multimode adornavit.

Abbatias quoque quasdam instauravit, unam siquidem in suburbio

Rothomagensi, in honore sancti Petri almique Audoeni (5), aliamque in

monte, qui dicitur Tumba (6), in veneratione archangeli Michaelis,

gregibusque monachorum insignivit. … Erat autem statura procerus,

vultu decorus, integer corpore, barba prolixa, cano decoratus capite,

piissimus monachorum amator, pauperum sustentator, orphanorum tutor,

viduarum defensor, captivorum redemptor.

(4) Dudon, IV, 126, p. 290-292. La dédicace de l’église de

Fécamp eut lieu en 990.

(5) Saint-Ouen de Rouen.

(6 ) Le Mont-Saint-Michel fut restauré en 965-966.

This roughly translates as:

XIX [ XIX ]

When Duke Richard was then (4) prosperous in the growth of many

good works, among many trades of the highest reputation, he built at

Fécamp a temple of wonderful size and beauty in honor of the Divine

Trinity, and adorned it in many ways with wonderful ornaments. He also

established certain abbeys, one indeed in the suburb of Rouen, in honor

of Saint Peter and the alms of Audoen (5), and another on the mountain,

which is called Tumba (6), in the veneration of the archangel Michael,

and he endowed it with flocks of monks. … He was also tall in stature,

handsome in appearance, healthy in body, with a long beard, and his head

adorned with gray hair, a most pious lover of monks, a supporter of the

poor, a guardian of orphans, a defender of widows, and a redeemer of

captives.

(4) Dudo, IV, 126, pp. 290-292. The dedication of the church of

Fécamp took place in 990.

(5) Saint-Ouen of Rouen.

(6) Mont-Saint-Michel was restored in 965-966.

The ecclesiastical history of England and Normandy by

Ordericus Vitalis vol 1 p381 (trans. Thomas Forester, 1853)

In the

year of our Lord 942, when Lewis was king of the Franks, Duke William

was murdered by the treachery of Arnulph governor of Flanders; and

Richard his son, then a boy of twelve years of age, became duke of

Normandy, and through various turns of fortune, some prosperous and some

adverse, held the dukedom fifty-four years. Among his other good deeds,

he founded three monasteries, one at Fecamp, dedicated to the Holy

Trinity,1 another at Mont St. Michel in honour of St. Michael

the archangel, and the third at Rouen in honour of St. Peter the

apostle, and St. Ouen the archbishop.

In the year of our Lord 996, on the death of Richard the elder,

he was succeeded by Richard Gonorrides his son,2

1

Richard I. founded a college of canons at Fécamp, the church of which

was dedicated in 990, but they were not replaced by monks till after the

year 1101, at which time also the abbey of St. Ouen was restored, and

therefore under Richard’s successor.

2 Gonnor was second wife of Richard I. For the

singular occurrences which introduced this lady into the ducal family,

see the continuator of William de Jumièges, book viii. c. 36.

The ecclesiastical history of England and Normandy by

Ordericus Vitalis vol 2 p299 (trans. Thomas Forester, 1853)

In the

year of our Lord 943, after Arnulph count of Flanders had slain William

Long-sword, duke of Normandy, and Richard son of Sprote, his son then

aged only ten years, had succeeded to the dukedom and received at Rouen

before his father’s funeral the homage and fealty of all the barons,

Lewis D’Outre-Mer, king of France entered Normandy with an army and

succeeded by fraud in carrying off the young duke to Laon, promising the

Normans on oath that he would bring him up as his own son, and have him

fitly educated in his royal court for governing the state. But things

turned out otherwise; for king Lewis, at the instigation of the traitor

Arnulph, resolved to put the boy to death, or at least to deprive him of

the power of bearing arms by amputating some of his limbs. Osmund, the

youth’s tutor, learning this from Ives de Creil,2 grand

master of the royal ordnance, he secretly persuaded Richard to feign

sickness, that he might thereby induce his guards to be less vigilant.

One day, while the king was at supper, and every one was engaged

in his own concerns or those of others, Osmond bought a truss of green

forage, and ascending the castle rolled it round the young duke. Then

descending the tower he made all haste to his quarters with the truss of

grass and spreading it before his horse, concealed the lad. When the sun

was set, he got out of the town, cautiously taking the prince with him,

and made for Couci where he gave him in charge to Bernard, count de

Senlis, his uncle.2

2 Bernard, count de Senlis and Valois, son of Pepin

II., a descendant of Charlemagne. He was not Richard’s uncle, but

cousin-german of the Duchess de Leutegarde, William Long-sword’s queen.

William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the kings of

England pp171-2 (ed. John Allen Giles, 1847)

[Emma] was the

daughter of Richard, earl of Normandy, the son of William, who, after

his father, presided over that earldom for fifty-two years, and died in

the twenty-eighth year of this king. He lies at the monastery of

Fescamp, which he augmented with certain revenues, and which he adorned

with a monastic order, by means of William, formerly abbat of Dijon.

Richard was a distinguished character, and had also often harassed

Ethelred: which, when it became known at Rome, the holy see, not

enduring that two Christians should be at enmity, sent Leo, bishop of

Treves, into England, to restore peace: the epistle describing this

legation was as follows:—“John the fifteenth, pope of the holy Roman

church, to all faithful people, health. Be it known to all the faithful

of the holy mother church, and our children spiritual and secular,

dispersed through the several climates of the world, that inasmuch as we

had been informed by many of the enmity between Ethelred, king of the

West-Saxons, and Richard the marquis, and were grieved sorely at this,

on account of our spiritual childen; taking, therefore, wholesome

counsel, we summoned one of our legates, Leo, bishop of the holy church

of Treves, and sent him with our letters, admonishing them, that they

should return from their ungodliness. He, passing vast spaces, at length

crossed the sea, and, on the day of the Lord’s nativity, came into the

presence of the said king; whom, having saluted on our part, he

delivered to him the letters we had sent. And all the faithful people of

liis kingdom, and senators of either order, being summoned, he granted,

for love and fear of God Almighty, and of St. Peter, the chief of the

apostles, and on account of our paternal admonition, the firmest peace

for all his sons and daughters, present and future, and all his faithful

people, without deceit. On which account he sent Edelsin, prelate of the

holy church of Sherborne, and Leofstan, son of Alfwold, and Edelnoth,

son of Wulstan, who passed the maritime boundaries, and came to Richard,

the said marquis. He, peaceably receiving our admonitions, and hearing

the determination of the said king, readily confirmed the peace for his

sons and daughters, present and future, and for all his faithful people,

with this reasonable condition, that if any of their subjects, or they

themselves, should commit any injustice against each other, it should be

duly redressed; and that peace should remain for ever unshaken and

confirmed by the oath of both parties: on the part of king Ethelred, to

wit, Edelsin, prelate of the holy church of Sherborne; Leofstan, the son

of Alfwold; Edelnoth, the son of Wulstan. On the part of Richard, Roger,

the bishop; Rodolph, son of Hugh; Truteno, the son of Thurgis.

Done at Rouen, on the kalends of March, in the year of our Lord

991, the fourth of the indiction. Moreover, of the king’s subjects, or

of his enemies, let Richard receive none, nor the king of his, without

their respective seals.”

The History Of The Norman Conquest Of England vol

1 pp206-7 (Edward A. Freeman, 1877)

§ 4. Reign of Richard the Fearless. 943-996.

William Longsword left one son, Richard, surnamed the Fearless,

born of a Breton mother Sprota, who stood, as we have seen, to Duke

William in that doubtful position in which she might, in different

mouths, be called an honourable matron, a concubine, or a harlot.1

Her son had been taught both the languages of his country, and he was

equally at home in Romance Rouen and in Scandinavian Bayeux.1

Whether his birth were strictly legitimate or not was a matter of very

little moment either in Norman or in Frankish eyes. If a man was of

princely birth and showed a spirit worthy of his forefathers, few cared

to pry over minutely into the legal or canonical condition of his

mother. The young Richard had been already, without any difficulty,

acknowledged by the Norman and Breton chiefs as his father’s future

successor in the duchy,2 and he now found as little

difficulty in obtaining a formal ininvestiture of the fief from his lord

King Lewis.3

1 See above, p. 180, and Appendix X.

1 See above, p, 192.

2 Dudo, 112 D.

3 Flod. A. 943. “Rex Ludowicus filio ipsius Willelmi,

nato de concubina Brittanna, terram Nortmannorum dedit.” So more fully

in Richer, ii. 34.

pp210-8

Great disturbances in Normandy followed on the unlooked-for death

of William Longsword. A new invasion or settlement direct from the North

seems to have happened nearly at the same time as the Duke’s murder; it

may even possibly have happened with the Duke’s consent. At any rate the

heathen King Sihtric now sailed up the Seine with a fleet, and he was at

once welcomed by the Danish and heathen party in the country. Large

numbers of the Normans, under a chief named Thurmod, fell away from

Christianity, and it appears that the young Duke himself was persuaded

or constrained to join in their heathen worship.2 …

Meanwhile the King marched to Rouen, he gathered what forces he could,

seemingly both from among his own subjects and from among the Christian

Normans; he fought a battle, he utterly defeated the heathens, he killed

Thurmod with his own hand, he recovered the young Duke, and left Herlwin

of Montreuil as his representative at Rouen.

… Lewis then,

according to this account, remains at Rouen, and a suspicion gets afloat

that he is keeping the young Duke a prisoner, and that he means to seize

on Normandy for himself. A popular insurrection follows, which is only

quelled by the King producing Richard in public and solemnly investing

him with the duchy. After this, strange to say, the Norman regents,

Bernard the Dane, Oslac, and Rudolf surnamed Torta, are won over by the

craft of Lewis to allow him to take Richard to Laon and bring him up

with his own children. The King is then persuaded by tlie bribes of

Arnulf to treat Richard as a prisoner, and even to threaten him with a

cruel mutilation. By a clever stratagem of his faithful guardian Osmund,

the same by which Lewis himself had been rescued in his childhood from

Herbert of Vermandois, Richard is saved from captivity, and carried to

the safe-keeping of his great-uncle, Bernard of Senlis.

… Harold, surnamed Blaatand, Blue-tooth or Black-tooth …

acted there as a disinterested friend of the Norman Duke and his

subjects. … Harold defeated Lewis in a battle on the banks of the Dive …

He passed through the land, confirming the authority of the young Duke,

and restoring the laws of Rolf.

2

Flod. A. 943; Richer, ii. 35. The Norman writers pass over their Duke’s

apostasy, which of course proves very little as to the personal

disposition of a mere child, though it proves a great deal as to the

general state of things in the country. But Flodoard and Richer are both

explicit. “Turmodum Nortmannura, qui ad idolatriam gentilemque ritum

reversus, ad haec etiam filium Willelmi aliosque cogebat.” (Flod.) “Ut.

… defunct! ducis filium adc idolatriam suadeant, ritumque gentilem

inducant.” (Richer.)

pp230-6

Richard wrought great changes within his own dominions, and he had many

enemies to contend against without; still the greater part of his reign

was no longer one incessant struggle, like the reign of his father and

his own early days. For some years wars and disputes went on almost as

vigorously as before; but for many years before his death Richard seems

to have enjoyed a time of comparative peace, which he devoted to the

consolidation of his power within his own states, and in a great degree

to the erection and enrichment of ecclesiastical foundations.

… The duchy of France, like the kingdom and the duchy of Normandy, now

passed to a minor. Hugh, surnamed Capet, the future King, succeeded his

father at the age of thirteen years. On account of his youth, he was

left by his father’s will under the guardianship of the Duke of the

Normans. Besides the close political connexion between the two princes,

Richard was betrothed to Emma, daughter of the elder and sister of the

younger Hugh, whom some years later he married.

p254

Richard, unlike

his father, was munificent in his gifts to the Church, especially to his

new, or rather restored, foundation of Fécamp and to the still more

famous house of Saint Michael in Peril of the Sea. The original

foundation of Fécamp was for secular canons. It was only in the days of

the second Richard that the Benedictine rule was introduced. Fécamp,

alone among the great monasteries of the Norman mainland, stands in the

land north-east of the Seine; all the rest lie either in the valley of

the river or in the true Norman districts to the west of it. Fécamp,

like Westminster, Holyrood, and the Escurial, contained minster and

palace in close neighbourhood; the spot became a favourite

dwelling-place of Richard in his later days, and it was at last the

place of his burial. The last years of his reign present only one

important event, a dispute, possibly a war, with the English King

Æthelred, a discussion of which I reserve for a place in the next

chapter in my more detailed narrative of English affairs. At last,

Richard the Fearless, Duke of the Pirates as he is called to the last by

the French historians, died of “the lesser apoplexy,” after a

reign of fifty-three years.

A biography of Richard, written for young readers is at The Little Duke, Or, Richard the Fearless

(Charlotte Mary Yonge, 1854).

21 November 996, in Fécamp,

Normandy, of “the lesser apoplexy”

Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book IV pp71-2 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914)

XX [XX]

His (1) et hujus modi boni odoris flosculis in laicali habitu

redolens gemma Christi egritudine corporis cepit vehementer aggravari.

Convocatoque Rodulfo comite, suo equidem uterino fratre, consilium

exigit de patriae dispositione. Qui nimio turbatus dolore, ac

aliquantisper factus elinguis novissime, consumpto spiritu, haec

responsa reddit duci: «Quamvis, dulcissime frater atque serenissime

senior, viribus corporis videaris destitui, tamen, dum in hac vita te

gaudemus amplecti, tuum est de totius patriae statu disponere.» Quo

audito, dux, suis undique optimatibus ascitis, Ricardum, filium suum,

coram exponit, hoc eum commendans et preficiens eloquio: «Hactenus,

commilitones optimi, vestrae militiae prefui; nunc, vocante Deo, morbo

crudescente, compellor a vobis separari. Proinde, si mei aliquando

amatores fuistis, oro vos ut hunc meum filium loco mei vobis

preferatis, eique fideles sitis, sicut mihi semper fuistis. Jam enim

me ingredientem viam universae carnis ulterius habere non potestis,

deposito onere vitae corruptibilis. His ab eo lugubre prolatis,

protinus tota domus concutitur gemitibus et lacrimis. Tandem, fletibus

sopitis, assensum prebent ducis voluntati, Ricardum adolescentem,

pacta ei fidelitate, equanimiter collaudantes principem. Dehinc,

languore ingravescente, lecto prosternitur, et, libratis sursum

oculis, inter verba orationis plenus dierum spiritum efflavit.

Huc usque digesta, prout a Rodulfo comite, hujus ducis fratre,

magno et honesto viro, narrata sunt, collegi; quae scolastico

dictamine conscripta relinquo posteris. Obiit autem apud Fiscannum

Ricardus dux primus, flentibus populis, gaudentibus angelis,

nongentesimo nonagesimo sexto anno ab Incarnatione Domini, regnante

Domino nostro Jesu Christo, qui cum Patre et Spiritu sancto vivit et

regnat in secula seculorum. Amen.

(1) Dudon, IV, 128.

This roughly translates as:

XX [XX]

With these (1) and this kind of fragrant flowers in a layman's

habit, the gem of Christ began to be greatly aggravated by the illness

of his body. And summoning Count Rodolfo, his own brother by blood, he

demanded advice about the disposition of his country. He, greatly

troubled by grief, and for a while rendered speechless, finally, having

exhausted his spirit, made these answers to the duke: "Although, most

sweet brother and most serene elder, you seem to be deprived of bodily

strength, nevertheless, while we rejoice to embrace you in this life, it

is yours to dispose of the state of the whole country." Upon hearing

this, the duke, surrounded by his nobles on all sides, presented

Richard, his son, before him, commending him and prefacing this speech:

"Thus far, my best fellow soldiers, I have been in charge of your

military service; now, at God's call, with a growing illness, I am

compelled to be separated from you. Therefore, if you have ever been my

lovers, I beg you to prefer this son of mine to yourself, and to be

faithful to him, as you have always been to me. For now you cannot have

me entering the path of the whole flesh any longer, having laid aside

the burden of a corruptible life. When he had uttered these mournfully,

the whole house was immediately shaken with groans and tears. At last,

their weeping having subsided, they gave their assent to the duke's

will, the young Richard, having promised him fidelity, and praising the

prince with equanimity. Then, his languor increasing, he prostrated

himself on the bed, and, lifting his eyes upward, amidst words of

prayer, he breathed his last, full of days.

I have collected up to this point the things that have been

narrated by Count Rudolf, the duke's brother, a great and honorable man;

which I leave to posterity, written down according to the dictates of a

scholastic. Now Richard, the first duke, died at Fiscan, with the people

weeping and the angels rejoicing, in the nine hundred and ninety-sixth

year from the Incarnation of the Lord, during the reign of our Lord

Jesus Christ, who lives and reigns with the Father and the Holy Spirit

forever and ever. Amen.

(1) Dudo, IV, 128.

|

The supposed tomb of both Richard I and

Richard II, inscribed with their names, at Fécamp

Abbey. However, in 2016, the

tomb was opened by Norwegian researchers who discovered that

the interred remains could not have been those of Richard, as

testing revealed that they were much older. Although it is not in

doubt that Richard was buried in the Abbey in 996, it is known

that his remains were moved within the Abbey several times after

his burial. |

at the monastery at Fécamp,

Normandy

Roberti

de Monte Auctarium A. 960-1052 in Monumenta

Germaniæ Historica vol 6 p478 (ed. G. H. Pertz, 1844)

996.

Obiit primus — secundus. Ipse Ricardus apud Fiscannum, pater Willermus

et Rollo avus apud Rothomagum requiescunt.

This roughly translates as:

996. The first died — the second. Richard himself rests at Fiscan, his

father William and his grandfather Rollo at Rouen.

- Orderici Vitalis Historiæ ecclesiasticæ libri

tredecim liber III vol 2 p9 (ed. Augustus Le Prevost,

1840); Medieval

Lands (RICHARD)

- Flodoardi annales in Monumenta

Germaniæ Historica SS 3 p405 (ed. G. H. Pertz,

1839); The ecclesiastical history of England and Normandy

by Ordericus Vitalis vol 1 p381 (trans. Thomas Forester,

1853); The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Richard I);

Medieval

Lands (RICHARD)

- Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book III pp33-4 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914); The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Richard I)

- Flodoardi annales in Monumenta

Germaniæ Historica SS 3 p405 (ed. G. H. Pertz, 1839); Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book IV pp68-9 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914); The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Richard I);

Medieval

Lands (RICHARD); Emma father from Flodoardi annales in Monumenta

Germaniæ Historica SS 3 p405 (ed. G. H. Pertz, 1839) and

Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book IV p68 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914); Emma died childless

from Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book IV p68 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914)

- Calendar of documents preserved in France vol

1 p250 (ed. J. Horace Round, 1899); Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book IV pp68-9 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914); Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges - Torigny) book VIII pp322-3 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914); The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Richard I)

- Calendar of documents preserved in France vol

1 p250 (ed. J. Horace Round, 1899); Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book IV pp68-9 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914); The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Richard I);

Medieval

Lands (RICHARD); wikipedia

(Richard I of Normandy)

- Children outside of

marriage from The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Richard I);

Medieval

Lands (RICHARD); wikipedia

(Richard I of Normandy)

- The ecclesiastical history of England and Normandy

by Ordericus Vitalis vol 1 p381 (trans. Thomas Forester,

1853); The History Of The Norman Conquest Of England vol

1 pp206-54 (Edward A. Freeman, 1877); The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Richard I);

Medieval

Lands (RICHARD); wikipedia

(Richard I of Normandy)

- Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book IV pp69-71 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914); The ecclesiastical history of England and Normandy

by Ordericus Vitalis vol 1 p381 (trans. Thomas Forester,

1853); William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the kings of

England pp171-2 (ed. John Allen Giles, 1847); The History Of The Norman Conquest Of England vol

1 pp206-54 (Edward A. Freeman, 1877); The Little Duke, Or, Richard the Fearless

(Charlotte Mary Yonge, 1854); Medieval

Lands (RICHARD); wikipedia

(Richard I of Normandy)

- Gesta Normannorum ducum (Guillaume de

Jumièges) book IV pp71-2 (ed. Jean Marx, 1914); Roberti de Monte Auctarium A. 960-1052 in

Monumenta Germaniæ Historica vol 6 p478

(ed. G. H. Pertz, 1844); exact date from Ex Obituario Gemmeticensi in Recueil

des historiens des Gaules et de la France vol 23 p422

(1876); The

Henry Project: The Ancestors of King Henry II of England (Richard I);

Medieval

Lands (RICHARD)

- Ademari Historiarum Liber III in Monumenta

Germaniæ Historica vol 4 p131 (ed. G. H. Pertz, 1841); Roberti de Monte Auctarium A. 960-1052 in

Monumenta Germaniæ Historica vol 6 p478

(ed. G. H. Pertz, 1844); William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the kings of

England p171 (ed. John Allen Giles, 1847); Medieval

Lands (RICHARD)

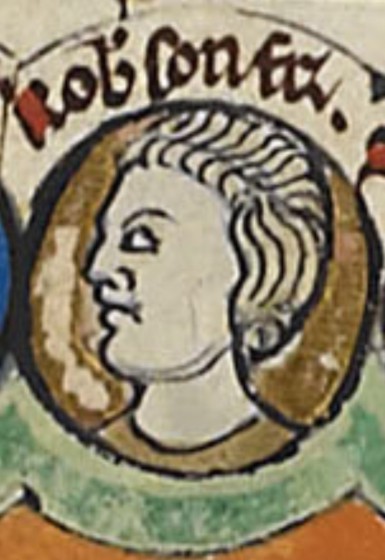

Richard II, Duke of Normandy

|

|

Richard II, duke of Normandy, as depicted

in the Genealogical chronicle of the English Kings (1275-1300) -

BL Royal MS 14 B V

|

|

Statue of Richard II "Le Bon" as part of

the Six Dukes of Normandy set of statues in the Falaise

town square, Normandy, France |

Richard I, Duke

of Normandy

Gunnor

Judith

of Brittany

This marriage contract established Judith's dowry.

Thesaurus novus anecdotorum vol 1 pp122-3

(Edmond Martène, Ursin Durand, 1717)

DOTALITIUM

JUDITHAE

comitiſſæ Normanniæ,

…… Conſtituta ſunt priſcorum ſanƈtione Patrum, & in utriuſque novi

ac veteris teſtamenti pagina invenitur ſcriptum … Creator omnium

legitimam conjunƈtionem viri ac mulieris præceperit, ſicut ſcriptum

eſt: Creavit Deus hominem ai imaginem & ſimilitudinem ſuam;

maſculum & feminam creavit eos, dum fabricavit Evam de una

ex coſtis viri ſui Adæ, & dixit: Quamobrem relinquet homo

patrem & matrem, adharebit uxori ſua, & erunt duo in carne

una. Ipſe Deus conditor omnium, quod dixerat diſponens. …

creſcite, & multiplicamini in finem, ſicuti per unigenitum Filium

ſuum Dominum Jeſum Chriſtum deſignavit, dum olim in Cana Galileæ

vocatus ad nuptias, pariter cum matre & diſcipulis venit idem

Redemtor, ipſaſque nuptias ſua præſentia ſanƈtificavit, & cum

adcumbentibus ſimul recubuit, & ibi aquam deificâ poteſtate,

propter amorem novæ, prolis, in vinum convertit; corda namque

diſcipulorum ſuorum inibi ad fidem roboravit, & anulum fidei in

ſuam ſanƈtam Eccleſiam per eoſdem manifeſtavit. Hinc quoque de duobus

legaliter nuptis in evangelio ait: fam non ſunt duo, ſed una caro;

Et, Quod Deus conjunxit, homo non ſeparet. Hinc etiam Paulus

apoſtolus viri ac mulieris conjunƈtionem corroborare volens, primùm

admonuit viros, dicens: Viri, diligite uxores veſtras, ſicut &

Chriſtus dilexit Eccleſiam. Mulieribus quoque præcepit ut viris

ſuis ſint ſubjeƈtae in omni caſtitate, bonitate, & honore. Cujus

exempli & auƈtoritatis inſtitutione edoƈtus, ego RICHARDUS in Dei

nomine cupiens per annorum curricula, diſponente pii Conditoris

clementiâ, habere liberos Deum timentes, adamavi te, ô dulciſſima

ſponſa, atque amantiſſima conjux JUDITHA, & à parentibus &

propinquis tuis expetivi te, & ſponſalibus ornamentis deſponſavi

te. Prætereà, legitimâ conjuƈtione expletâ, in dote tua dono tibi,

donatumque in perpetuùm eſſe volo, in pago videlicet Siſoienſe

Brenaïco cum appendentibus ſuis, ſcilicet Campols, Katorcias,

Fraxinus, Grandem-campum, Til, Cambrenſe, Fererias, Villa Remigii,

Folmatium, Sanƈtus Albinus, Laubias, Maitgrant, Kahin, Novum Maſnile,

Pons, Manneval, Tortuc, Sanƈtus Leodegarius. Item Til, Valenias,

Corbeſpina, Fait, Laubias, Villa Audefridi, Karentonus, Campflorem,

Fontanas, Belmont, Belmontel, Litulas, *Cebeſias in ſupradiƈtis villis

XX. & unam, molendinos XXVIIII.

tredecim carrucas boum, cum ſervis, & omni ſupelleƈtili earum, cum

pratis, ſylvis, terris cultis & incultis, exitibus &

reditibus, aquis, aquarumve decurſibus, piſcatoriis, & quidquid

inibi pertinere videtur. In vicariam quoque Cingatenſem concedo tibi

has villas: Cingal, Urtulum, Fraſnetum, Bretevilla, Ofgot, Maſnil

Coibei, Maſnil Robert, Avavilla, Merlai, Petrafica, Maſnil Anſgot,

Til, Peladavilla, Longum Maſnile, Novavilla, Corteleias, Corteletes,

Sanƈtus Audomarus, Villa Petitel, Boſblancart, Novum-manſum, Aſcon,

Bruol, Torei, Donai, Donaiolum, Villare, Matreles, Combrai,

Longavilla, Placei, & in ſupradiƈtis villis eccleſias XV.

farinarios XV. cum terris cultis & incultis,

aquis, aquarumve decurſibus, exitibus & reditibus, viis &

inviis, ſylvis, pratis, paſcuis, & quidquid ad ſupradiƈtas villas

pertinere videtur, abſque ullius contradiƈtione. In vicaria inſuper

quæ vocatur Kelgenas concedo tibi has villas quæ ita nominantur:

videlicet Trelvilla, Rolvilla, Flamenovilla: item Flamenovilla,

Fegelvilla: item Rolvilla, Kalvilla, Benediƈti villa, Nova-villa,

Cantapia, Geroldi villa: item Geroldi-villa, Solomonis-Villa,

Longavilla, Brotavilla, Fagum: item Nova-villa, Bixrobot, Sottevilla,

Sanƈtus Chriſtophorus, Seroldivilla, Stobelont, Bojo-rodevilla,

Rodulfi-villa, Maſnile, Manuine, Englebertvilla, Sotenvaſt, Sanƈtus

Martinus cum quatuor villis, Colecleſia, Starletof: item

Engilberti-villa, Virandevilla, Caſuetum, Herardi-villa, Bruet,

Huntolf, Tobec, Waſt, Fraxenus, Beroldwaſt, Reginavilla, Bruet,

Huntolf, Tober, Waſt, Fraxinus, Beroldwaſt, Reginavilla, Ketevilla XVII.

eccleſias, XV. quoque molendine, cum terris cultis

& incultis, aquis, aquarumve decurſibus, pratis, paſcuis, ſylvis,

& quidquid inibi pertinere videtur. Concedo inſuper tibi jure

proprio & familia naea quingentos utriuſque ſexus. Et ut hæc omnia

quæ ſupra diximus in perpetuùm poſſideas, & vera eſſe credantur,

& inconvulſa omni tempore permaneant, hunc propriæ dotis libellum

diſcribere juſſi, ac manu propriâ ſubterfirmare decrevi.

This roughly translates as:

THE DOWRY OF JUDITH

Countess of Normandy,

…… They were established by the ancient sanction of the Fathers, and on

the page of both the New and Old Testaments it is found written … The

Creator of all things has ordained the lawful conjunction of man and

woman, as it is written: God created man in his own image and

likeness; male and female he created them, when he fashioned Eve

from one of the ribs of his husband Adam, and said: For this cause

shall a man leave his father and mother, and shall cleave to his wife,

and the two shall be one flesh. God himself, the Creator of all

things, having ordained what he had said. … grow, and multiply unto the

end, as he designated by his only-begotten Son the Lord Jesus Christ,

when once in Cana of Galilee, called to the wedding, the same Redeemer

came with his mother and disciples, and sanctified the wedding itself

with his presence, and lay down with those who were reclining, and there

he turned water into wine by divine power, for the love of the new,

offspring; For he strengthened the hearts of his disciples therein to

faith, and manifested the ring of faith in his holy Church through them.

Hence also he says of two legally married people in the gospel: they

are no longer two, but one flesh; And, What God hath joined

together, let not man put asunder. Hence also the apostle Paul,

wishing to strengthen the union of man and woman, first admonished men,

saying: Husbands, love your wives, even as Christ also loved the

Church. He also commanded wives to be subject to their husbands in

all chastity, goodness, and honor. Taught by whose example and